| Previous | Index | Next |

![]()

discovered that a tennis ball is on the racket approximately four milliseconds. Four one-thousandths of a second. Human reaction time is 120 milliseconds or more, so that ball is long gone before anybody feels it. It is off the racket even before the racket gives." Such a sharp jolt obviously packs a great deal of energy into the briefest of moments. "The muscles can't react to it, so the elbow, which is a single plane joint and can't pass any of the shock along, can briefly receive a hundred times the force it does when you throw something. No wonder people get tennis elbow."

The tennis ball study was commissioned by a manufacturer who will use the results to design balls that remain on the racket longer. But Ariel was most fascinated by having to devise a new equation to describe the behavior of elastic objects colliding at oblique angles, because these didn't seem to follow textbook physics. "The point of maximum compression is not the point of maximum force," he says excitedly. The commercial overtones of the research did not hold his interest. "They talk about light balls, heavy balls. Such craziness. All the brands were so much the same it was like they were made by the same machine."

Because so many of the body's reverberations end up in the feet, Ariel has long been interested in athletic shoes. "That is the witchcraft business, for sure," he says. "Shock absorption is the key to better distance running, no question, but look." He flips through a book of data. "Some brands absorb 2,300 newtons, some only 1,000. That range! And the manufacturers don't even know what their own shoes do."

Ariel, using an exquisitely sensitive $25,000 force plate, which transmits readings of four kinds of pressure-vertical, forward, sideways and twistingto an oscilloscope, charted the forces of footstrike in different shoes at every point of foot placement. "You see pictures of runners, it looks like they're landing on their heels, but they're not. The good ones don't. They flick the foot down flat at the last instant. All these companies are making wonderful heels and the best runners are never coming down on them." One company, Pony, bowed to Ariel's advice and has brought out a shoe tested in his lab.

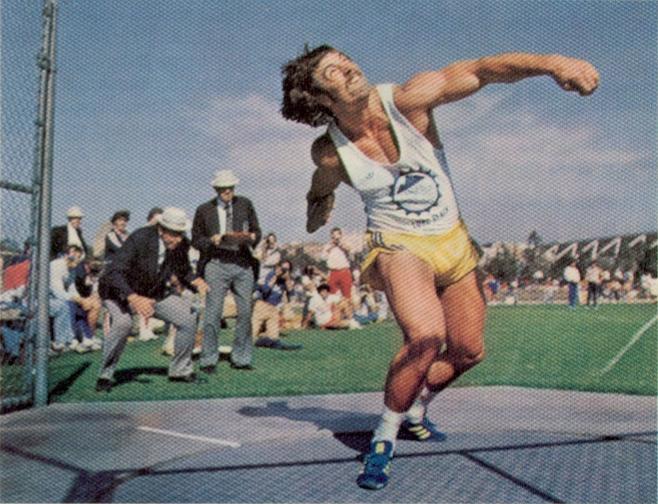

Visiting Ariel's office and laboratory, tucked away in a storefront between Erik's Giant Subs and Radio Shack, one sees wonders everywhere, like the electronic display on which he can call up the style of a shotputter or quarterback in the form of a sequence of glowing green stick figures. "You have to be very responsible to change the form of any good athlete," he says. "The better the athlete, the more it seems wrong to fool with him." So Ariel has programmed

the computer to fool with an electronic copy of the athlete instead, changing angles, timing, even weight, and with each change he computes how performance would be affected. Seeing that, the imagination goes spinning off into a giddy future, where performance can be predicted years in advance, where technique and training can be fitted to individual talents. It turns out that Ariel is already disappearing into that future.

"We examined film of Dick Fosbury winning the Olympic high jump in 1968 and of Valery Brumel jumping his earlier world record of 7' 5%". We found that of the total forces generated, the flop style has a higher vertical component. The computer had Brumel use the flop. Had he known about it when he was jumping, Brumel could have

cleared 7' 11 ". So we will one day see an eight-foot high jump."

Bud Greenspan, who produced The Olympian series on PBS television, provided Ariel with slow-motion film from 1936. He wanted to know who was the better sprinter, Jesse Owens or Eddie Hart, the present coholder of the world record for 100 meters at 9.9 seconds. Owens had run 10.2 on cinders, without starting blocks, Hart on polyurethane, with blocks, but Ariel saw no

problem. "We knew the angular displacements, so we knew how many degrees per second their ankle, hip and knee joints displaced. We knew the length of the bones and the speed of the film frames, so we knew how much distance was covered per second. We let each man cover 100 meters and computed the time it took him." The winner? Jesse Owens.

The precision with which Ariel's machines can trace movement patterns has widespread application in injury prevention and treatment. "Any little pain will change the pattern of locomotion," he says. Just now, Ariel has finished an analysis of film sent by the Dallas Cowboys, who wanted to find out if injured players were returning to normal patterns.

The possibilities for rehabilitation, or

continued

57

![]()

| Previous | Index | Next |